Data Drought and Data Flood

Contributed by Mark Trigg*.

It’s hot, and very, very dry. The rains have failed, and the animals are dying.

Photo by Mark Trigg

Around the table people are concerned that it will be people dying next. The cycle seems to repeat every 10 years and the response is exactly the same, every time – we must do something and save lives. “Drill more boreholes and put in big pumps and generators”, someone cries, “no matter the cost!”. A timid voice rises above the ongoing discussions “but that was only a temporary solution last time, there are pump houses full of broken generators and pumps from each funder, so how will this be different!?”. Yes, everyone agrees, but we need to save lives now! The voice persists, “Will there be enough water to sustain the boreholes in the future, and will the tens of thousands of cattle coming for the water, destroy all the slow growing arid vegetation around the new boreholes?”. “Yes”, says the chair of the meeting, “these are all important things – you have until tomorrow’s meeting to find the answers and then we act!”.

This scenario was to repeat in various different guises over the early phases of my career in emergency aid and development as a water resource professional. Making rapid decisions involving people, their livelihoods, and complex hydrology/hydrogeology, but with next to zero data or knowledge of the area. My MSc had equipped me with the technical skills to undertake essential calculations, such as estimating groundwater recharge, but finding relevant local data to do those calculations was always a challenge. Surely someone must have some data, I asked myself?

Fast forward 20 years…….

The water challenges are just as acute, perhaps even more so. What excites me now are all the new global hydrology datasets (both from models and remote sensing) that hold the promise of providing the data needed for the many water management challenges we are facing – such as the one above. On the flip side, what also annoys me most are the many claims in academic papers that, this or that shiny new dataset will solve, such and such a water issue, with no evidence that that will be the case – just that surely it should, as you can download it here. However, when I talked to decision makers involved in water resource issues, they were very rarely aware of these potentially useful datasets – and even if they were, they often did not have the time, skills or bandwidth to download and process these datasets for their specific question. The so called “last mile” problem.

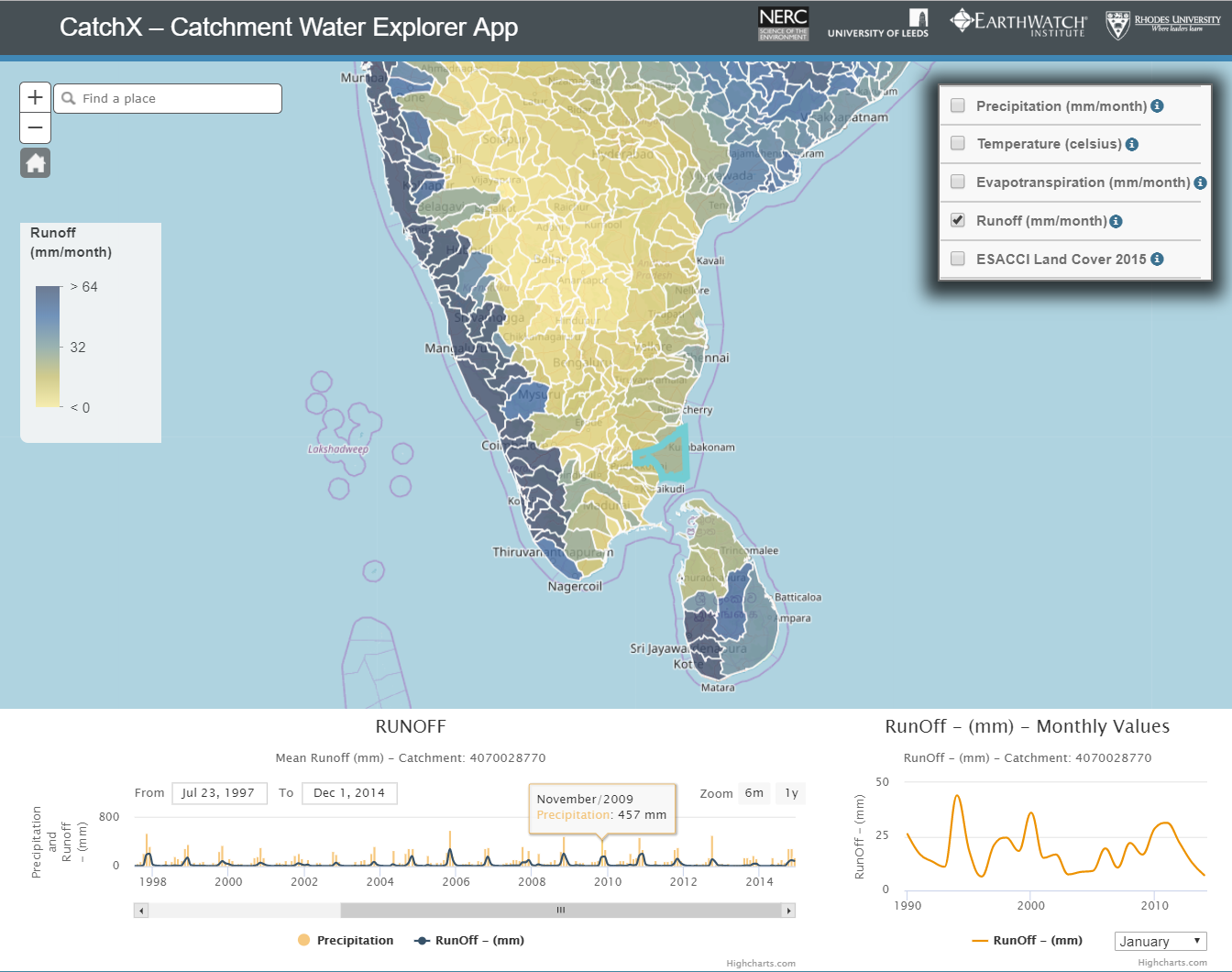

So, with innovation funding from the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and in partnership with Earthwatch and IWR, we at water@leeds set out to create a global hydrology data web platform called CatchX. The aim of CatchX is to provide cutting-edge hydrological water balance data at any location in the world in an easy to access form that users can use directly without lots of processing. We selected and processed some of the best hydrology datasets currently freely available and processed them into about 57,000 river catchments globally. Users can easily visualise and download hydrological data for their catchment of interest and also compare it with other catchments. Take a look and see what you think – we would love to get your feedback.

Does it solve the last mile problem? Not necessarily, but it is an experiment to bridge the gap between data developers and potential users of the data. Testing the platform with users in South Africa showed it has value, but also highlighted credibility questions of using some of the data at the catchment scale (particularly runoff). You can find all the platform reports at the bottom of this page.

Where next? Well, the increasing plethora of datasets out there and ensuing access challenges probably means as a community we need to pay more attention to these aspects than we have done in the past. However, academically, there is often more career value in creating yet another dataset! This only compounds the problem for users of our data. Yes, these datasets are important and have huge potential, but not by default. Who is responsible for this data gap/flood, and are we doing enough as a community to bridge it? I do acknowledge that there are many of us already engaged in these aspects of our science, such as communicating uncertainty, citizen science etc., and I am certainly not the first to voice these issues. However, I still think it worth throwing down the gauntlet – Do you want your data to change the world or just impress your academic colleagues?

*Author

Mark Trigg is a University Academic Fellow in Water Risk at the School of Civil Engineering, University of Leeds, UK.

Credits

CatchX builds on your data as a hydrological community, so we are very grateful for all your efforts. Credit also goes to: Wim Clymans from Earthwatch; Luis Velasquez also from Earthwatch, who used his wizardry to build the platform; Susana Almeida, who trawled through the hundreds of datasets available and designed the processing; Denis Hughes and Jane Tanner from IWR, who tested the platform against local data in South Africa; and Klaudia Schachtschneider from WWF South Africa for a superbly productive user workshop.

If you are interested in more information about the scenario at the start of this blog, you can find it here: Trigg, M., Gibson, J. and Rowney, M., 2004. Addressing sustainability and the environment during emergency drought relief in Moyale, north Kenya. Water and Environment Journal, 18(4), pp.217-221.

0 comments