Understanding public responses to flood warnings

Contributed by Michael Cranston, RAB Consultants, Scotland

The Winter 2015 floods in the United Kingdom and Ireland led to severe and widespread flooding for many communities. The introduction of storm naming by the Met Office and Met Eireann the same year has since led to the names of Desmond, Frank and Eva becoming synonymous with the flooding that was experienced during that winter. Storm Desmond (5 December) brought major flooding to Cumbria and southern Scotland with a new 24-hour UK rainfall record of 341.4 mm being recorded at Honister Pass in Cumbria. Storm Eva (24 December) brought further flooding to parts of northern England, whilst Storm Frank (29/30 December) brought severe damage to communities in Newton Stewart and Ballater.

Severe flooding from the River Dee in Ballater (Source: Evening Express)

This series of major floods led to a UK Government review on National Flood Resilience which is summarised by Louise Arnal in this HEPEX article on what we should learn from the winter 2015 floods. However, the UK has seen significant investment in improved flood forecasting in the 10 years post-Pitt and this account of the short and medium range forecasts ahead of Storm Frank highlights that flood forecasting tools and models are starting to support much earlier warning of significant flooding impacts.

Flood alerts and warnings in Scotland are now sent to over 25,000 members of the public since the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) introduced the new service in 2011. During the Winter floods, SEPA’s service saw 300,000 individual messages being issued to alert and warn of potential flooding. Following this, SEPA, through the Centre of Expertise for Waters (CREW), subsequently commissioned research to understand public responses to warnings and to assess how effective the flood warning service is for reducing the impacts of flooding.

A research team at the School of Social Sciences the University of Dundee were commissioned to undertake this project in 2016. The primary method of collating information on public response was through a web-based questionnaire of registered customers of the service. This survey was designed to assess associations between multiple customer characteristics, including location, type of message received, prior experience of flooding, risk awareness, and demographics. 1341 customers provided a response to the survey invitation, and crucially 1290 of those provided a postcode to allow for geocoding of their responses. The information provided through the questionnaire response was further enhanced through several community group meetings held by the research team.

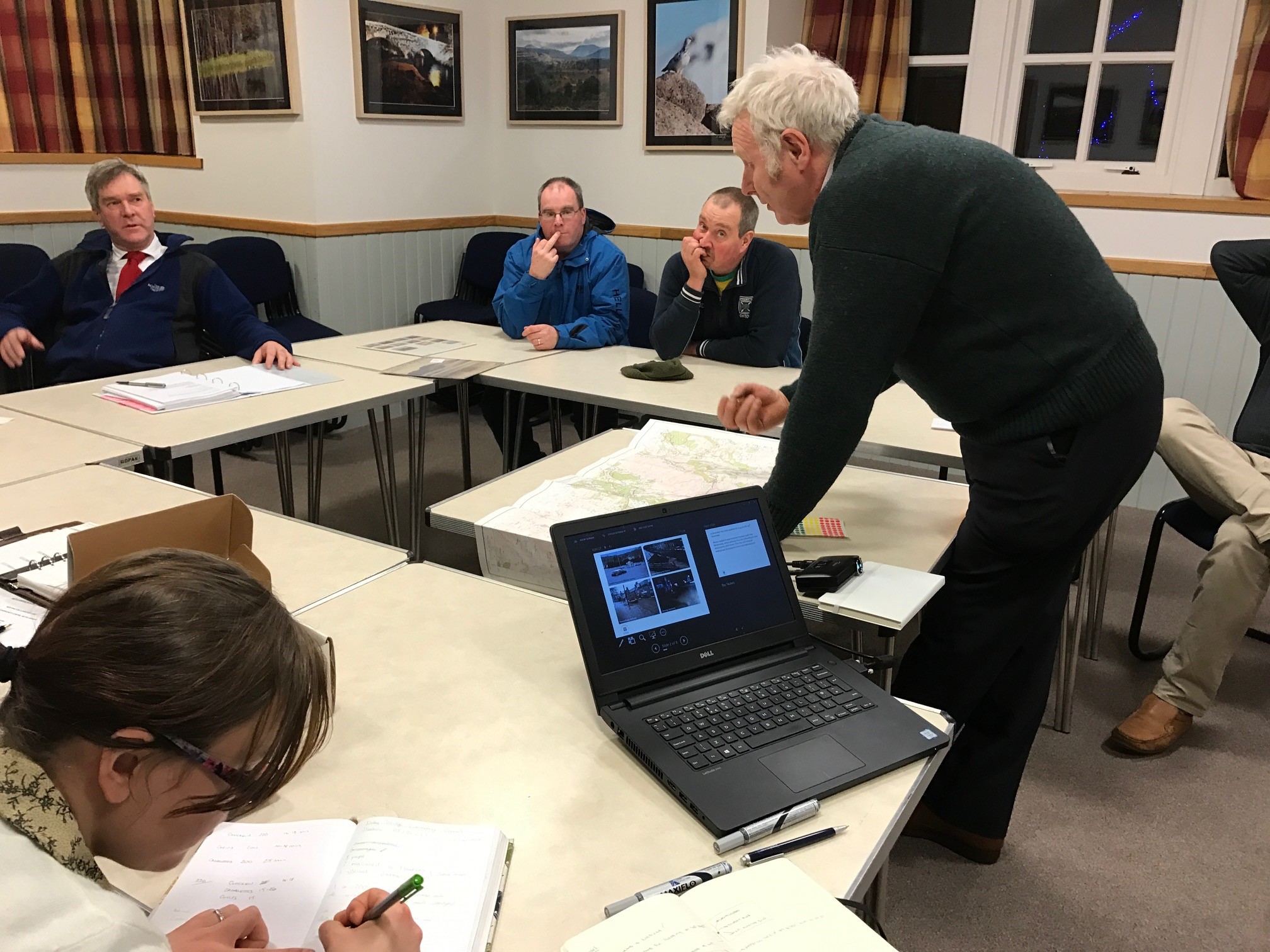

The research to understand public responses to flood warnings involved consultation with members of the public and community groups across Scotland, including this taken in the Speyside

The research results are starting to deliver some interesting findings around the public response to flood warnings. It is clear from the results that the service is valued by those at risk of flooding with 66% of the respondents satisfied with the warnings they are provided. Many take mitigating actions, of note: 62% of those who said flooding of land was important to them subsequently moved livestock on receipt of a warning; 71% of those that stated they had bought these measures, deployed property level protection; and 42% of all respondents at some time removed vehicles on the receipt of a warning.

Less effective elements of the service focus on those members of the public that are not engaged with the service, possibly the ‘flood unaware’ and elements that are not locally specific enough to encourage action. For example, the least content of customers are those that do not receive regular messages. Also, those who receive regional Flood Alerts are less likely to act given the lack of locally specific information, which is typically misunderstood by members of the public as a part of the service that they consider should offer more local relevant flooding information. This theme was one of several that were explored further during the community workshops with some referring to the need for local reference points in warnings, a discussion which featured as part of the flood memory and historical references HEPEX article last year.

Work continues to conclude this research which will be published by CREW this summer with recommendations for future development of the flood warning service. However, a summary of the results will be provided at the forthcoming EGU General Assembly as a PICO presentation as part of the Hydrological Sciences Division, in co-organization with the Natural Hazards Division, on a session of the Hydrological Forecasting Sub-Division on operational forecasting and warning for natural hazards.

This work will be presented as part of the PICO session on operational forecasting and warning systems for natural hazards: PICO spot A, Wednesday 26th April between 08:30 and 12:00 (see programme here)

This work would not have been possible without the efforts of the Dundee University research team of Dr. Alistair Geddes, Dr. Andrew Black and Alice Ambler and the guidance of SEPA’s Project Manager Cordelia Menmuir.

Michael Cranston is an Honorary Research Fellow with the School of Social Sciences at Dundee University and a consultant in flood early warning with RAB Consultants in Scotland. Prior to this he was an operational flood forecaster and Manager of the Flood Forecasting and Warning team at SEPA.

0 comments