For discussion: Have we reached the limits of what can be forecast in water, weather and climate?

Contributed by Tom Pagano, a HEPEX guest columnist for 2014

The opinions expressed here are solely the author’s and do not express the views or opinions of his employer or the Australian Government.

This post invites a discussion around the topic “Have we reached the limits of what can be forecast in water, weather and climate?”

On 28-29 October, Australian researchers in an offshoot of the Global and regional Energy and Water Exchanges (GEWEX) project will meet in Canberra to examine the water and climate information needs for tomorrow and compare these to the current state and developments in information services, observation sources, scientific knowledge and model technology. One of the six sessions is on forecasting, addressing the question above.

There are two sides to this topic:

- Are our model forecasts achieving skill levels close to the theoretical maximum imposed by unavoidable uncertainties, e.g. chaos?

- And how far is the skill achieved by the research community from what is found in operations?

Of course, an ancillary issue is if we even know the theoretical limits? In weather and climate there have been many experiments on predictability, but have comparable experiments been done for hydrology? For soil moisture and snow there have been some but what about runoff? There are some contributions, such as Maurer and Lettenmaier, 2003; Berg and Mulroy, 2006; Mahanama et al., 2008; Wood and Lettenmaier, 2008; and Mahanama et al., 2011, but global-scale assessments such as Alfieri et al, 2013 are only just now happening.

Then there are questions about if we even know the quality of the operational forecasts? Public evaluations of as-issued operational hydrologic forecasts are rare but examples exist (such as the Mekong and US National Weather Service). For about a century, Western US seasonal water supply outlooks have been produced statistically, relating springtime snowpack to summer runoff. The longest lead forecasts improved when El Nino was introduced as a predictor (although short-lead forecasts were unchanged). Methodologically, the process was upgraded with the adoption of Principal Components Regression (which handled predictor covariance, Garen 1992) and later Z-Score regression (which handled missing and incomplete data, Pagano et al 2009). The National Weather Service also started using hydrologic simulation models to generate ensemble forecasts.

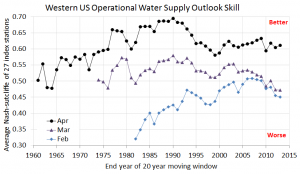

Despite this, Pagano et al. (2004) showed that operational forecast skill had, at that time, fallen to levels not seen since the 1950s. This drop was likely mostly the result of climate variability and change.

Operational seasonal water supply forecast skill by leadtime (the top line is forecasts issued in April, the bottom those issued in February). The target is often April-July or April-September, depending on the location. The index is the spatial average of Nash Sutcliffe indices at 27 long-term stations for a 20-year moving window of forecasts. The period shown includes as-issued forecasts from 1941-2013. (Updated from Pagano et al. 2004)

All this extra technology made it easier to make forecasts, streamlined their automation/rapid updating, helped with difficult catchments with short records, made new products possible (e.g. ensembles), and increased available lead times (forecasts, albeit highly uncertain, are now made up to 18 months in advance), but all this did not do much for the skill of the core product (April-July runoff predicted a month or two ahead).

Is this a case where the limit has been reached and we can’t expect much more?

Note that it is entirely acceptable (even desirable) to know if our potential in a certain field has been reached. We can refocus effort and investments towards creating and communicating a greater diversity of products, possibly on different time scales or of different variables. It also makes it all the more powerful for when we do identify low hanging fruit, full of potential.

What do you think? Where have we reached/not reached the limits of what can be forecast in water, weather and climate? What areas are full of untapped potential?

Make your voice heard in the comments below!

0 comments