The model, the forecast and the forecaster

by Jan Danhelka, a HEPEX 2015 Guest Columnist

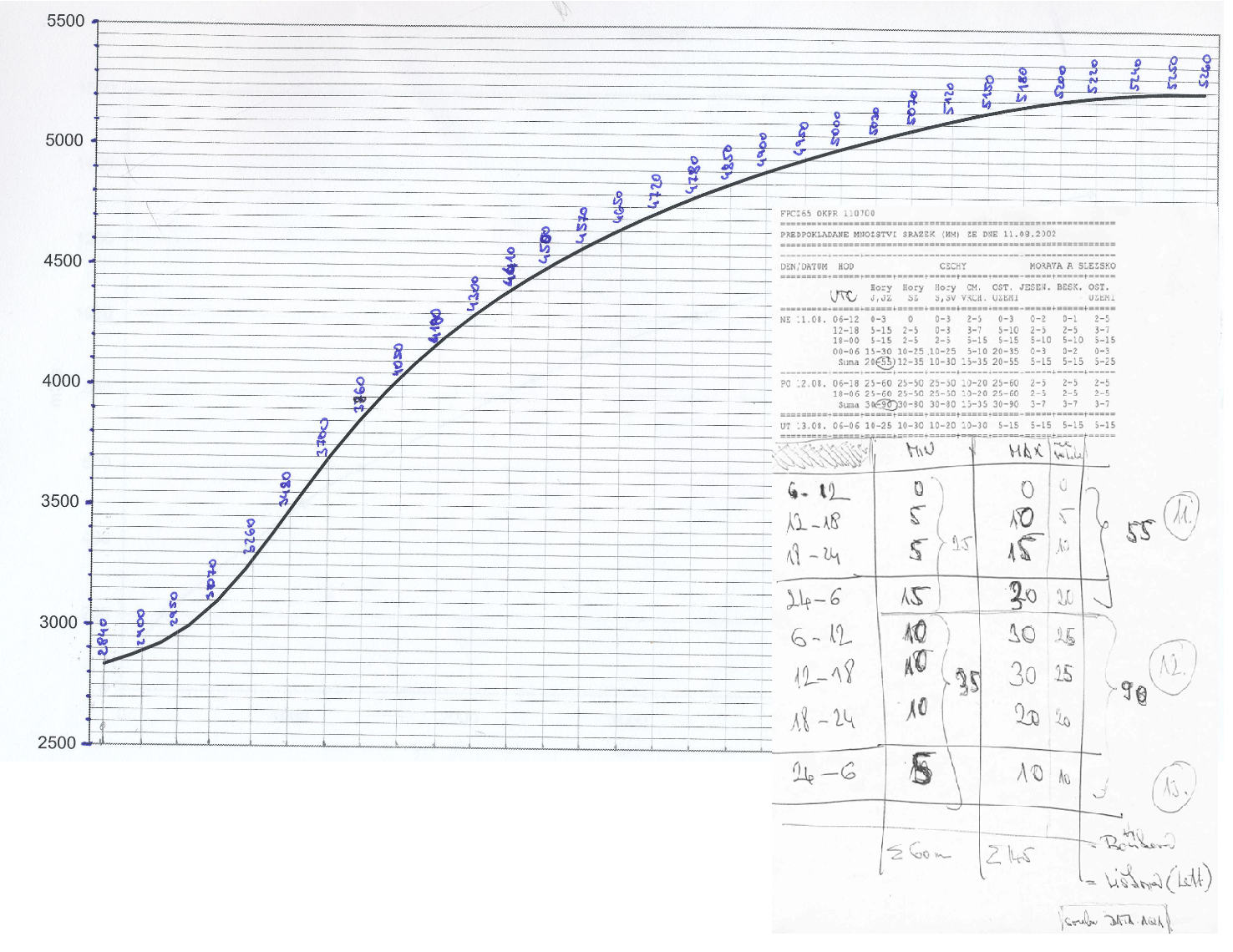

I have to start my first HEPEX blog post by a short introduction of myself. I have more than 10 years of experience in real time hydrological forecasting and modelling. Those years (un)fortunately included quite a few large (in some cases truly catastrophic) floods of different nature including the 2002 large scale summer flood, the 2006 winter flood and many flash floods events, in particular in 2006 and 2009. What I have learned was that every flood is specific and surprising in some of its aspects.

When it comes to me, I consider myself to be a practician, not a hard scientist. In addition, I like to ask provocative questions and provide controversial answers and I don’t mind to play the devil’s advocate. Going back to the issue of flood forecasting, let me start in far history.

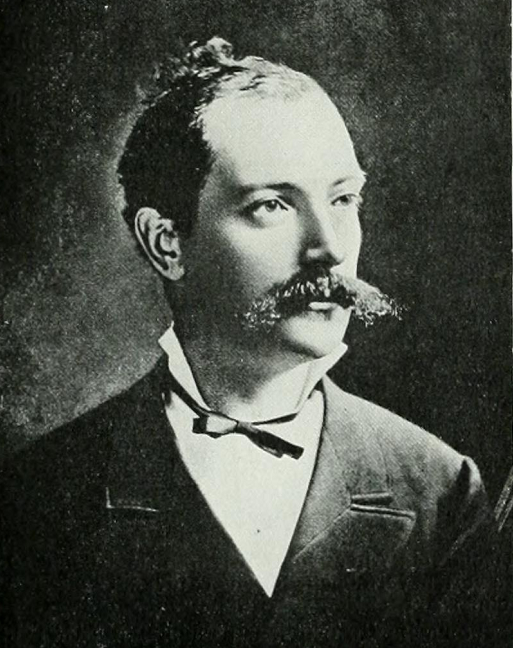

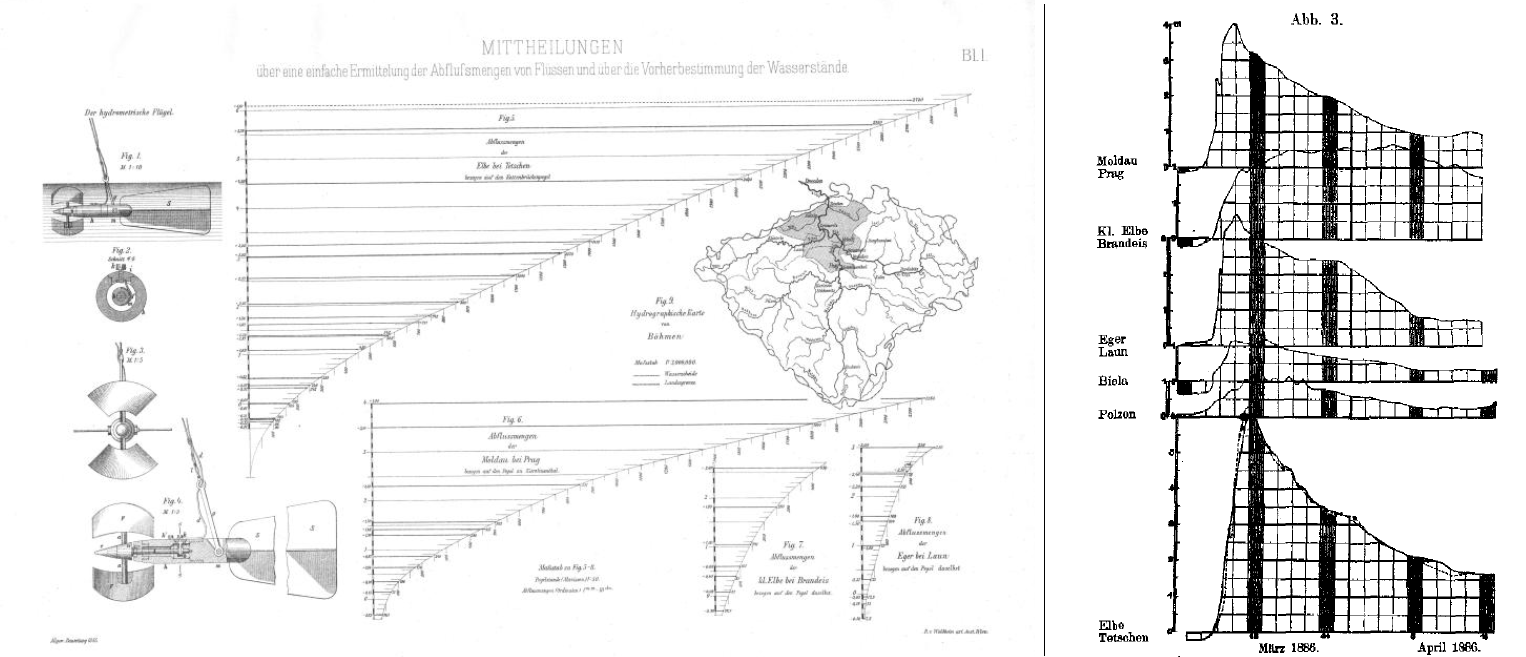

The Hydrological Service in Bohemia was established in 1875 (we are celebrating 140 years this summer) making it one of the oldest such services in the world.

The head of the service, Prof. Harlacher, published his novel method of forecasting based on discharges and travel times in 1886 and 1887. To my knowledge, it was the first conceptual forecasting method in the world, as previous methods, e.g. for the Seine River in Paris, used just statistical methods to estimate changes in water stages based on changes in water stages and in precipitation upstream. By the way, Harlacher’s method started to be used operationally in 1892, after the telegraph reports of water observation were exempt from charges (and is used until today, in parallel to hydrological models).

I gave this large introduction to illustrate the long history of forecasting under different conditions and circumstances. I have joined the Czech Hydrometeorological Institute in the time of the implementation of models into every day forecasting practice, so I have experienced the initial distrust of forecasters as well as their discovery of the possibilities of this new tool. I have realized then that new model implementations cannot succeed without the full support from the forecasters.

We have moved in time and a lot of research has been done; obviously, the future of hydrological forecasting is in probabilistic modelling and multi-models. From my point of view, these approaches are fantastic, except one little thing – the role of the forecaster.

Lets have a look at the analogy in weather forecasting. It seems to me that the old generation of weather forecasters, who based their forecast on the synoptic analysis, knowledge and experience without meteorological model outputs, was replaced with the generation that grew up in the age of NWP models.

Forecasters are fully trained in the use of the model but, more and more, they tend to accept the model as a source of information similar to the measured data, and become fully dependent on it. Unfortunately, some forecasters, not all of them nor the majority of them, have turned to be the interpreters (skilful and educated) of model outputs, and perceive the model as a given black box think, created somewhere in a previous step of the forecasting chain (again similar to e.g. radar estimates or satellite pictures – someone else’s job and responsibility).

The forecaster experience then tends to be more about the model behaviour than the behaviour of the atmosphere over the given area (they know that COSMO has overestimated temperature for the last three days by 2°C, but they do not think about the physical process in reality). It happens to me several times that when I ask “What will be the precipitation in the next two days?”, the response I get starts with “Well, models say…”, instead of “Well, the synoptic situation is…” or “The wind flows from…”.

I remember a HEPEX workshop in Italy a couple of years ago. Someone (probably Eric Wood) presented a result from another workshop where a question was raised (not the precise wording): “What would you prefer to have in order to achieve skill in forecasting?” a) a better model, b) better data, c) a “better” forecaster. Participants there voted for better data (they were mostly modellers and model developers, so they trusted their models very much and they tried to make automatic modelling systems without a forecaster, therefore the vote for better data was not surprising). It was John Schaake who said “I would prefer a better forecaster”. I absolutely agree with John.

One of the specifics of the real time forecasting is immediate verification of your forecast (in opposite to e.g. climate change modelling). Everyone who prepares a forecast knows the unpleasant feeling you have when facing the reality completely different from what you have forecasted few hours ago. Typically, one tries to find what was wrong and what she could/should done better. However, I think the situation is a bit different if you ran the model, tried to tune the parameters, to optimize the estimation of initial conditions, or to interact with the model somehow on one hand, or if you simply received the model output to interpret it. In the first case, you think about model and real processes and your own knowledge of these. The reflection in the second case is obviously a bit different.

The progress in modelling technology cannot be stopped (nor there is any reason to do that), however we should not lose the forecaster and her/his role from our scope when developing a new forecasting system, to prevent the turn from ‘forecaster’ to ‘forecast interpreter’.

I do not know a solution nor have an idea on how to do that, but I am fully convinced that hydrologists/forecasters should be kept in the heart of the process; they should remain the ones who make the forecasts. If you have an idea let me know.

Let me finish this post with a quotation of Vít Klemeš from his marvellous book “Common sense and other heresies”:

“The modelling technology has far outstripped the level of our understanding of the physical processes being modelled. Making use of this technology then requires that the gaps in the factual knowledge be filled with assumptions which, although often appearing logical, have not been verified and may sometimes be wrong.”

“The modelling technology has far outstripped the level of our understanding of the physical processes being modelled. Making use of this technology then requires that the gaps in the factual knowledge be filled with assumptions which, although often appearing logical, have not been verified and may sometimes be wrong.”

That is why we need a forecaster to be skillful, experienced, and why a forecaster should understand well the model structure and its limitation.

March 13, 2015 at 14:39

Great post. During the big flood events I’ve worked, the key decisions makers want to get decision support directly from the forecasters. The models and data often become unreliable when the flooding approaches or exceeds record levels. At this point, forecaster experience in how to assimilate all the information, know what is useful and what to throw out, consider alternate techniques and historical analogs and then quickly make choices on how to come up with a ‘best’ forecast under the circumstances is what matters most. I’m all for model and data improvements. But if I had to choose, I would also choose the better forecaster. The forecaster is the key ingredient without which great service is impossible to achieve. (Note: The opinions expressed are mine personally and do not necessarily represent NOAA’s or National Weather Service’s positions, strategies, or opinions)

March 13, 2015 at 16:04

Very nice post! Could I add another fantastic Klemeš quote: “There is a general agreement that historic records do not contain enough information on the upper tails of flood distributions; that these – to repeat the 50-year-old blunt statement of Professor Moran – can only be guessed. My claim is that frequency analysts pretend to be able to elevate such guesses to the status of ‘‘scientific estimates’’ by substituting for the unknown (complex and, for all we know, perhaps even undefined) probability distributions of real floods simple known ‘‘models’’ and performing the estimations for them. The latter exercise, while it can be completely irrelevant to the real floods, is of course formally quite legitimate since the models are precisely defined and all their features are knowable from their definitions. But I consider it misleading to present such ‘‘systematic procedures’’ as ‘‘flood estimation’’ (and regard them as ‘‘powerful analytical tools’’) – they are merely estimations of models that themselves are only guesses and, moreover, often guesses that deliberately ignore some of the known (and crucial) evidence in the interest of mathematical convenience. I simply repudiate the notion that one can transform dubious guesses into scientific inferences by ‘‘mathematical prestidigitation,’’ to use Moran’s words once more.”

From: Closure to ‘‘Tall Tales about Tails of Hydrological Distributions, I and II’’ by Vít Klemeš, Journal of Hydrologic Engineering, Mar/Apr 2002.

March 16, 2015 at 14:53

Great article and very cleverly written. The analysis of past and common focus is excellent. One comment I may add is that forecasting floods faces other challenges besides the modeling and the numerical prediction. It goes through a series of goals to achieve. The first is being able of predicting the weather. Then comes predicting the response of the watershed in terms of peaks and volume of runoff. And finally, the end goal is to forecast where will be the inundation (flood maps, aerial extents of floods, flood levels, and duration of inundation). So the forecaster, as mentioned by the author of this great article, needs to look beyond numbers and automated outputs, and think ahead of the models.

March 16, 2015 at 22:09

Hello Jan, we met at the EMS meeting last autumn when you showed us around your workplace.

Only because you wrote that you like to ask provocative questions, provide controversial answers and not mind to play the devil’s advocate do I dare to put out the “against the current” comment that the educations of forecasters, both hydrological and meteorological are out of date.

They were designed before the computers and aimed at purely manual/subjective forecasting. When the computer models arrived it was thought that if only the forecasters knew how the models worked they would be able to modify the output.

But it hasn’t worked out. There is nothing wrong to know how the automatic gear box in your car is constructed, but does it make you a better driver? From my time at ECMWF monitoring their model I learned that it was more or less impossible to judge the reliability of a certain forecast even we knew the forecast system in every detail*)

The only exception is short term forecasts. Fresh observations the computer hasn’t got (late arrival or not assimilated) may enable the forecasters to nudge the computer output in the right direction.

My recipe, as I have lectured the last 3-4 years, is to realize that forecasters, whether they like or not, act as “intuitive statisticians” trying to make sense of a flow of information.

In some sense, you brought it up yourself when you wrote: ”The forecasters know that COSMO has overestimated temperature for the last three days by 2°C, but they do not think about the physical process in reality”.

The problem is statistical. The first spontaneous approach would be to deduct 2ºC from the current forecast. But are three days enough? And if they are, can we be sure that the mean error is not dependent on the temperature, i.e. the weather regime? It is very difficult and time consuming to analyse the physical reasons behind such a mean error.

This approach was formalized in my Kalman filter system presented in

http://old.ecmwf.int/publications/member_states_meetings/Forecast_products_users/Presentations2008/Persson.pdf

Slides 6-21 contain the main information and in slides 36-37 I show, just to demonstrate the potential of the system, how it can make good temperature forecasts for the Slovakian lowland (Červená) using ECMWF output from a distant location in the Czech highland (Piešťany).

So we need to enlarge our knowledge by a feeling for statistics. I will come back to that . . . .

*) Only when the ensemble system was put in operation did we get a fair chance to judge the reliability – and it is not a coincidence that the EPS is a STATISTICAL forecast system